How to Write a Matrix in Latex

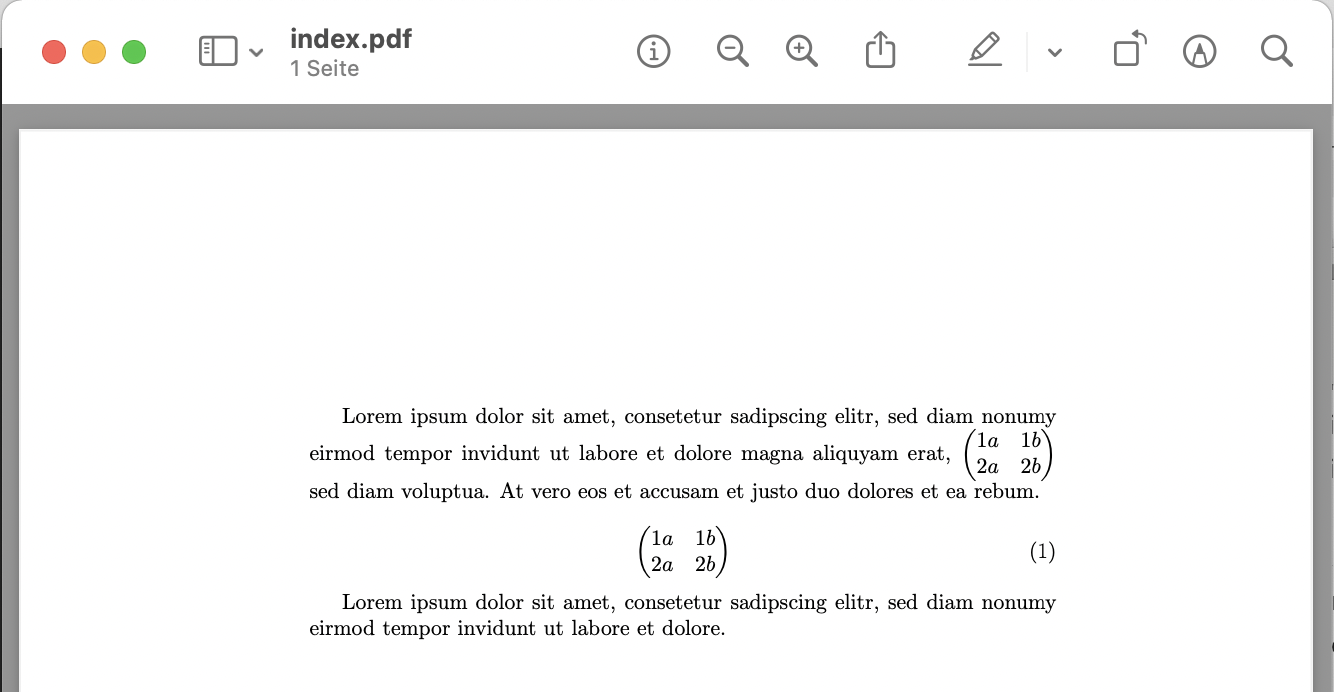

You can write a matrix in LaTeX as inline equation (in the middle of a floating text) or as block equation (as a new section). Listing 1 shows the LaTeX code of both variations. The resulting PDF is shown in figure 1. Pay attention to the second line of the example, it includes the amsmath package which is required to use the matrix commands. The pmatrix key word is just one possible matrix form. See table 1 for all supported matrices styles. To use a different style you just have to replace pmatrix in the \begin{pmatrix} and \end{pmatrix} command.

For inline matrices you might also consider using the smallmatrix command (see listing 2for a complete example). Which behaves the same just makes the matrix smaller.

\documentclass[10pt]{article}

\usepackage{amsmath}

\begin{document}

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consetetur sadipscing elitr,

sed diam nonumy eirmod tempor invidunt ut labore et dolore

magna aliquyam erat, (egin{pmatrix} 1a & 1b \ 2a & 2bend{pmatrix} ) sed

diam voluptua. At vero eos et accusam et justo duo dolores et ea rebum.

\begin{equation}

\begin{pmatrix}

1a & 1b \\

2a & 2b

\end{pmatrix}

\end{equation}

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consetetur sadipscing elitr,

sed diam nonumy eirmod tempor invidunt ut labore et dolore.

\end{document}

\begin{smallmatrix}

a & b \\

c & d

\end{smallmatrix}| LaTeX Code | Result |

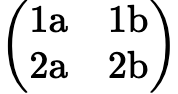

|---|---|

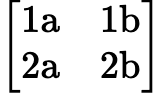

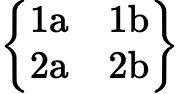

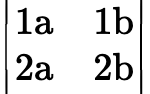

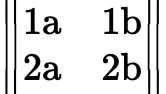

\begin{matrix} 1a & 1b \\ 2a & 2b\end{matrix} |  |

\begin{pmatrix} 1a & 1b \\ 2a & 2b\end{pmatrix} |  |

\begin{bmatrix} 1a & 1b \\ 2a & 2b\end{bmatrix} |  |

\begin{Bmatrix} 1a & 1b \\ 2a & 2b\end{Bmatrix} |  |

\begin{vmatrix} 1a & 1b \\ 2a & 2b\end{vmatrix} |  |

\begin{Vmatrix} 1a & 1b \\ 2a & 2b\end{Vmatrix} |  |

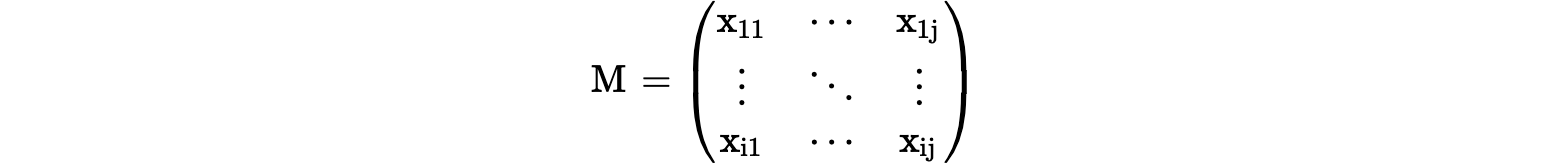

Denoting a Matrix with Dots (cdots, ddots, vdots)

Often you have to describe large matrices or matrices with an undefined end. For this purpose you can use the LaTeX commands \cdots, \vdots and \ddots. See equation 1, 2 and 3 for an example. In table 2 you see a description of the LaTeX dot commands.

M = \begin{pmatrix}

x_{11} & \cdots & x_{1j} \\

\vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\

x_{i1} & \cdots & x_{ij}

\end{pmatrix}

| LaTeX Command | Type |

|---|---|

\cdots | Horizontal dots above the line |

\ldots | Horizontal dots on the line |

\vdots | Vertical dots |

\ddots | Diagonal dots |

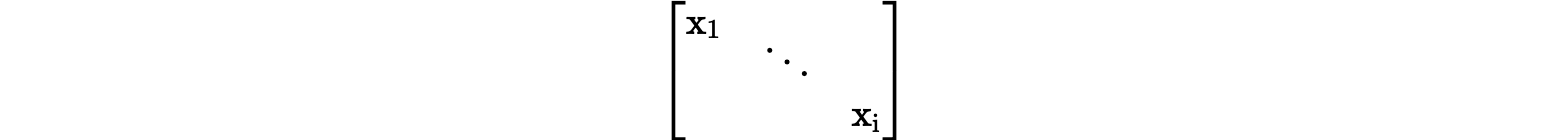

Matrices With the Array Command

As an alternative to the matrix command you can also use the array command to achieve similar results. If you want to have parentheses around the array you can wrap the array between \left[ and \right] for square brackets or \left( and \right) for normal brackets. Listing 4 shows and example with square brackets.

\left[ \begin{array}{rrr}

1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1 \\

\end{array}\right]Using the array command gives you the possibility to control the spacing between the matrix components/cells. This is handy if you have more complicated terms in your matrix (e.g. fractions). Increasing the spacing makes it look better and the symbols of the matrix cells do not overlap. Listing 5 illustrates a working example. Pay attention to the begingroup and endgroup command. If you do not specify them it will change the stretch for the all arrays in the document which are placed after this command.

\begingroup

\renewcommand*{\arraystretch}{1.5}

\left[ \begin{array}{rrr}

1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1 \\

\end{array}\right]

\endgroupA Matrix with Sections

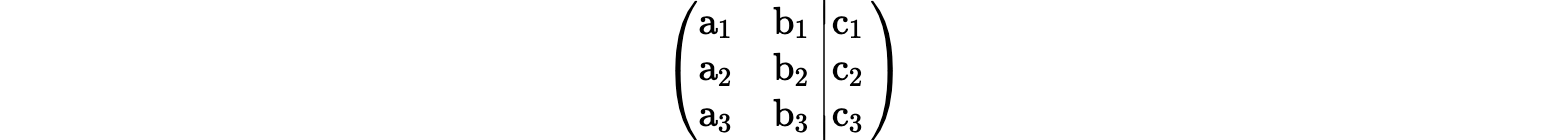

If you use the matrix command which does not render parentheses around the matrix, you can combine two matrices and have a vertical dividing line between them (via \left| and \right. command). You can then wrap the whole construct with \left( and \right) again to have parentheses around the combined matrix.

\left(

\begin{matrix}

a_1 & b_1 \\

a_2 & b_2 \\

a_3 & b_3

\end{matrix}

\left|

\begin{matrix}

c_1 \\

c_2 \\

c_3

\end{matrix}

\right.

\right)